July 20, 2012 — When the fraud-busting unit of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) publishes an analysis of physician behavior, questions naturally arise as to whether some sort of crackdown on physician misbehavior is around the corner.

Case in point is a report issued in May by that dreaded HHS unit, the Office of Inspector General (OIG). The OIG found that from 2001 to 2010, physicians increased their use of higher-level — and more lucrative — billing codes for evaluation and management (E/M) services in the course of treating Medicare patients. During that time, the volume of Medicare payments for E/M services rose 48%, whereas spending for all Medicare Part B goods and services increased 43%. In 2010, E/M services accounted for 30% of all Medicare B expenditures.

The coding trend of up, up, and away held true across 13 different categories of E/M services, which include new patient office visits, initial and subsequent inpatient hospital care, emergency department visits, and initial and subsequent nursing home care. In each E/M category, there are from 3 to 5 Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) billing codes for differing levels of complexity.

The same pattern of physicians picking higher-level CPT codes emerged between 2001 and 2009 for 2 categories of consultation visit codes that were eliminated in 2010.

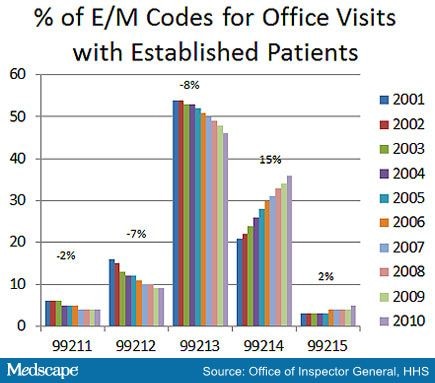

This pattern is perhaps best illustrated in the bread-and-butter category of office visits for established patients, which has 5 tiers of complexity. This category accounted for 48% of Medicare payments for E/M services in 2010.

|

In 2001, office visits for established patients coded 99211, 99212, and 99213 accounted for 76% of the visits in this category, with the remaining 24% tagged with 99214 or 99215. By 2010, the percentage of visits with the 3 lower codes had decreased to 59%, and 99214 and 99215 visits had risen to 41%.

The most dramatic changes occurred with 99213 and 99214 visits. In 2001, the midrange 99213 visit represented 54% of the pie, and the 99214 visit, 21%. In 2010, the share for 99213 had slipped to 46%, whereas that for 99214 stood at 36% — a 15% increase over 2001.

The jump from 99213 to 99214 yielded a handsome increase in compensation. In 2010, Medicare paid on average $97.35 for a 99214 visit, which is 50% more than the $64.80 for a 99213.

The OIG states that it did not determine whether physicians who chose more 99214s and other higher-level E/M codes in 2010 billed Medicare inappropriately or fraudulently. That line of inquiry, it says, will be the focus of future reports.

At the same time, "E/M services have been vulnerable to fraud and abuse," the OIG notes. In other words, some physicians who should have billed a 99213 instead have gone 1 level higher to garner an extra $32.55.

Medscape Medical News interviewed several figures in the healthcare industry who are familiar with medical coding to get their take on the trend reported by the OIG. By and large, they said there are other explanations besides fraud and abuse. Still, the ever more common 99214 is symptomatic of a fee-for-service payment system and its foibles.

Sicker Patients or Better Charting?

One suggested but unproven explanation for higher E/M coding says that Medicare patients are sicker than they were in 2001, forcing physicians to work harder at diagnosing and managing their conditions.

"An aging population means more complex care," said Frank Cohen, MPA, a statistician and data analyst who heads a practice management consulting firm in Clearwater, Florida. "And we've seen a significant increase in obesity, which is driving a rise in adult-onset diabetes."

Coding expert Betsy Nicoletti agrees.

"Patients are on so many medications now, and they're complex," said Nicoletti, author of The Field Guide to Physician Coding and The Physician Auditing Workbook. "The medications and chronic diseases you have play into medical decision making. So a lot of those patients from a medical decision perspective audit as a [99214], and then you have to get into the history and exam that goes with it."

Another theory for higher E/M coding — and widely touted — is that physicians have come to master the arcane rules of coding created by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), thanks to books and classes such as Nicoletti's.

"Can you find me a physician who hasn't been to an E/M training class?" she said.

The rationale for E/M training looks like this: In the past, busy physicians were prone to underdocument both the patient's condition and the tests and procedures they performed or ordered. Because patient charts were sketchy, they could not justify picking a code — a 99214, say — that accurately described the patient encounter. So they chose a 99213 to play it safe and settled for lower reimbursement in the process. And even if they did thoroughly capture the visit in their notes, they often might go with a 99213 to avoid the accusation that they were overcoding, especially if they were hazy about CMS coding rules. As any practice management consultant would say, such physicians "left money on the table."

Undercoding has been an especially bad habit for primary care physicians who depend on E/M services for the bulk of their income in an era of stingy third-party reimbursement. So the push has been, ostensibly, to turn undercoders not into overcoders, but merely accurate coders. That spirit of fair play informs the headline of a trade magazine article in 2001 titled "How to Get All the 99214s You Deserve." Such education has helped physicians more thoroughly document what they do for their patients and injected them with the confidence to choose the right code.

However, responsible coding coaches have cautioned physicians against turning things upside down, such as taking a more extensive history or making a more detailed exam and documenting all of it simply for the sake of a higher E/M code. Nicoletti and others stress that medical necessity forms the basis for the 3 components of an E/M service: the history, the exam, and medical decision making. If someone presents with a hangnail, the visit will not warrant a 99214, no matter how much a physician does for the patient and no matter how much he or she writes down in the chart.

An article published in the New England Journal of Medicine last year warned about the problem of getting it backward. "Some clinicians are tempted to engage in extraneous clinical activity to justify using higher code levels and reaping excessive payments," the authors stated.

EHRs Put E/M Coding on Steroids

Experts say electronic health record (EHR) technology also has helped to elevate 99213s to 99214s by dint of its super-charting capabilities. "The use of EHRs has made it easier to document a higher level of service," said Nicoletti.

Consultant Frank Cohen said there is nothing wrong with physicians benefiting from this digital tool. "If they document more efficiently or more completely, it doesn't mean they're coding wrong," he said. "They're coding more accurately."

The economics of better coding are not lost on EHR vendors. They advertise that undercoding physicians who buy their systems become accurate coders — and enjoy a revenue bump as a result.

The EHR edge is not just a matter of improved documentation of a physical exam or a medical history. Some EHRs will even suggest the E/M code that the physician should select. After all, a computer can remember the complex criteria for arriving at an E/M code better than a human (eg, how many body systems must be reviewed, or how many elements of a medical history must be taken).

Some EHRs go a step further. In addition to scoring a physician's documentation for an E/M code, the system will identify elements of history, exam, and medical decision making that would boost the code a level higher if they were performed and recorded.

These capabilities — E/M coding on steroids, as it were — have set off alarm bells. A set of guidelines on EHR use in the Office of Billing Compliance at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center — the kind of bureaucracy created to avoid federal fraud and abuse charges — warns that computers are good at tallying components of a history and exam, but they cannot calculate medical necessity. A human must do that.

"Code selection tools," the guidelines state, "can create a trap for the unwary provider who relies solely on the code selector without evaluating the medical necessity supporting the reason for the visit (chief complaint and history of present illness) and the type of documentation in the EHR." Furthermore, "it would be inappropriate to use a code prompt...to suggest that additional data be added for the sole purpose of increasing an E/M code level without being medically necessary."

The guidelines also warn about the ability of EHRs to "take over the documentation for the provider" and pump it up. Three common EHR features make this possible:

- Exploding elements: A physician clicks on "GI Exam," and the software automatically supplies the text of all standard GI findings such as "abdomen soft and tender, normal bowel sounds," never mind if the physician fails to listen to someone's belly.

- Default to Negative: The software automatically describes all items within a review of systems, history, and physical exam as negative unless a physician documents a positive finding for any of them. Again, the technology can make a physician look as if he or she put in work that never happened.

- Cloned Documentation: EHRs allow physicians to recycle documentation from a previous patient encounter into a new one, whether through a cut-and-paste function or another function such as "copy note forward." In the process, physicians may sign off on misleading and inaccurate information. For example, the cloned documentation may include a test or procedure that was not performed in the latest visit.

The point person for EHRs at the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) acknowledges that these software capabilities can lend themselves to abuse, but emphasizes that fraud has more to do with the human at the keyboard.

"If you want to be fraudulent, you can use computer technology just as you could with paper charts," said Steven Waldren, MD, director of the AAFP's Center for Health Information Technology.

Gaming the System or Just Following the System?

Like consultant Frank Cohen, Dr. Waldren said that the trend toward higher-level E/M codes generally stems from physicians coding more accurately for services that were previously undercoded.

The message from Dr. Waldren and other experts interviewed byMedscape Medical News is that the OIG should not blame physicians for getting better at picking codes; after all, they are just playing by the rules.

"Are physicians gaming the system, or are they following the system?" asked healthcare information technology consultant Mark Anderson, based in Montgomery, Texas.

By following the system, Anderson refers to 2 different sets of E/M documentation guidelines published by CMS, one in 1995, the other in 1997. Physicians must adopt one or the other. If an honest application of the guidelines results in higher levels of E/M coding, and if CMS objects to that, the agency should simply revise its rules, said coding consultant Nicoletti.

Cohen expresses doubt about the ability of the OIG to pin the charge of overcoding on physicians, given the murkiness of the CMS guidelines. They are so unclear that when professional coders are asked to select an E/M code for a given patient visit, they disagree more than 40% of the time, he said.

"I don't want to hear from the government that there is an issue with doctors coding incorrectly when the guidelines are nebulous," said Cohen.

Cohen also said the OIG report on coding trends is full of "junk research." For one thing, it contains government data not accessible to researchers like him, he said. "It's impossible to validate."

He finds it incredible that the OIG excluded physicians who billed fewer than 100 E/M services to Medicare per year and claimed that they represented 30% of all physicians who provided E/M services to seniors.

"Do you believe that a third of physicians had fewer than 100 E/M visits?" Cohen said. "It would be 8 patients per a month. Why would you want to eliminate a third of all physicians? That biases the study. And why is the threshold fewer than 100?"

Warning Shots and Network Deselection

Cohen's criticisms of the OIG report notwithstanding, the issue of E/M overcoding has been on the radar of CMS and private health insurers for years, and understandably so. The dollar amounts involved are huge.

A CMS report on improper payments in 2010, for example, found that of the top 10 service categories in Medicare B with the highest amount of estimated erroneous payments, 6 were E/M services. Number one was office visits with established patients, at almost $1.5 billion. CMS based its estimates on a review of sampled claims.

Of the erroneous payments for office visits with established patients, the vast majority represented overpayments, as opposed to underpayments. CMS estimated that overpayments for 99213 and 99214 visits alone that year came to roughly $1.1 billion. Tellingly, CMS reported that 36% of the nearly $1.5 billion in overpayments for office visits with established patients stemmed from overcoding, or picking a code higher than the documentation warranted.

For now, the OIG is refraining from attributing the wide scale shift from 99213s to 99214s to outright fraud and abuse. However, its report on coding trends did fire a warning shot. The OIG stated that it had identified 1700 physicians across the country who billed Medicare at the 2 highest tiers within an E/M visit category — think 99214s and 99215s — a remarkable 95% of the time in 2010. Their patients, in terms of leading diagnoses, closely resembled the patients of physicians whose E/M coding followed a more traditional bell curve, but their average Medicare payment per E/M service was nearly 49% higher. In addition, their average total payment per Medicare patient was 92% more.

The OIG recommended that CMS review these 1700 top-heavy E/M coders and, if their claims turn out to be "inappropriate," recover the overpayments. CMS replied that it would turn over the names to its Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs), which process claims, with instructions for each MAC to focus on the 10 highest billers in their jurisdiction.

CMS justified its proposed limited review by saying that the agency and its MACs must consider the return on investment for its policing work. The cost of reviewing an E/M claim can easily exceed the $43 overpayment associated with the average E/M error. In setting priorities for its recoupment efforts, CMS and MACs must balance the low stakes of E/M services with the high stakes of more costly Medicare services, the agency said.

At the same time, CMS has already put overcoders on notice. In June, the agency sent a Comparative Billing Report to 5000 physicians who consistently bill at high E/M levels. This report, which CMS characterizes as educational, as opposed to punitive, compares the recipient's coding patterns with those of other physicians so he or she can spot potential billing errors.

One private health insurer, Aetna, has gone beyond friendly reminders about selecting the right E/M code. Earlier this year, Aetna notified 130 Texas physicians that it was dropping them from its network because their E/M coding, and the use of level 4 and 5 codes in particular, made them too costly to retain.

Dr. Waldren of the AAFP said there is a simple resolution to the E/M coding controversy: reforming how physicians are paid.

"Hopefully in the next several years, we'll move to paying physicians based on quality as opposed to quantity," he said. "It won't be an issue of whether I documented a visit to the right [E/M] level.

"It will be an issue of whether my patient with diabetes is doing better."

Interestingly not much has changed in 10 months since this article was written. We just cannot get out of the fee for service, hamster on a wheel mentality.

ReplyDeleteVery good article. It's an interesting addition to my inquiry about billing and insurance. Thank you very much.

ReplyDeleteCheck this out too:

Medisoft Program